Last year at the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) conference, one of the premier academic conferences in the field, a team of researchers from Princeton and Ulm published a technique they developed to ricochet (“relay”) radar off of surfaces and around corners. This is a neat paper, and I have connections to both universities, so I saw this in a bunch of different places.

The research focuses on non-line-of-sight (NLOS) detection — detecting objects and agents that are hidden (“occluded”). People have been trying to do this for a while, with varying levels of success. There are videos on YouTube that seem to indicate Tesla Autopilot has some ability to do this on the highway, for example when an occluded vehicle two or three cars ahead hits the brakes suddenly. However, since Autopilot isn’t very transparent about its sensing and decision-making, it’s hard to reverse-engineer its specific capabilities.

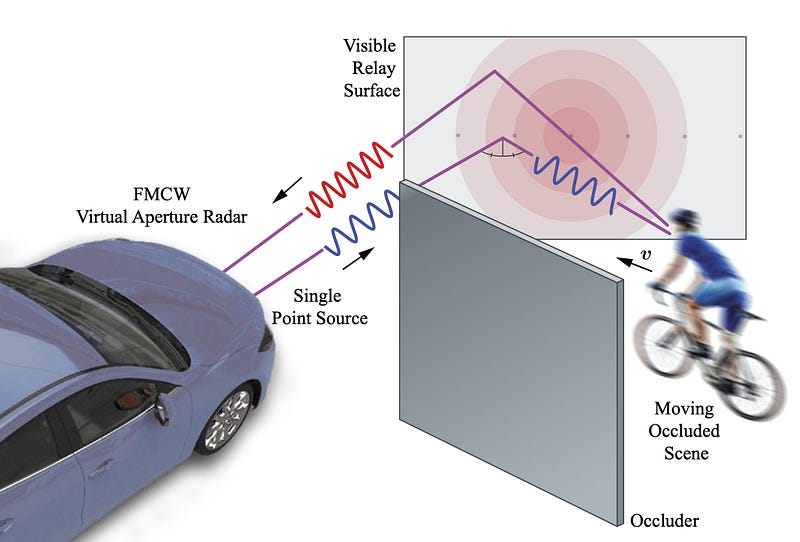

The CVPR paper uses bounces radar waves off of various surfaces and uses the reflections to determine the position of NLOS (occluded) objects. The concept is roughly analogous to the mirrors that sometimes get put up to help drivers “see around” blind curves.

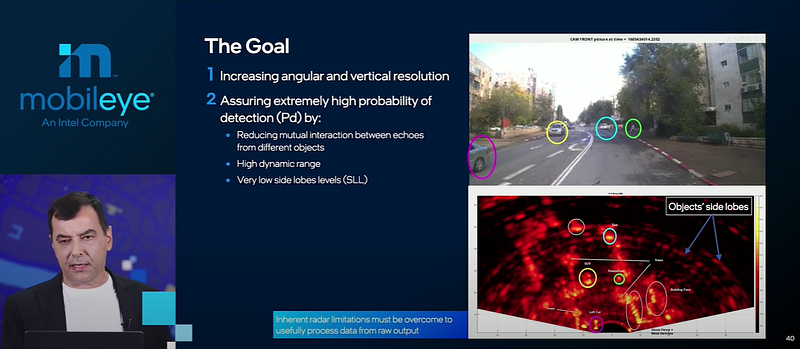

This approach seems simultaneously intuitive and really hard. Radar waves are already notoriously scattered and detection is already imprecise — trying to detect objects while also bouncing radar off an intermediate object is tricky. The three-part bounce (intermediate object — target object — intermediate object) requires a lot of energy. And filtering out the signal left by the intermediate object adds to the challenge.

How do they do it?

They use a combination of the Doppler effect and neural networks. The Doppler effect allows the radar to measure the velocity of objects. The system can segment objects based on their velocities, figuring out which objects are stationary (these will typically be visible intermediate objects) and which objects are in motion. Of course, this means that NLOS objects must have a different velocity than the relay objects.

The neural network is used in a pretty typical training and inference approach.

Some of the math in this paper stretches my knowledge of the physical properties of radar, but ultimately a lot of this seems to boil down to trigonometry:

Surfaces that are flat, relative to the wavelength λ of ≈ 5 mm for typical 76 GHz-81 GHz automotive radars, will result in a specular response. As a result, the transport function treats the relay wall as a mirror…

The result of the math is a 4-dimensional representation of an NLOS object: x position, y position, velocity, and amplitude of the received radar wave.

The researchers used lidar to gather ground-truth data for the NLOS objects and draw bounding boxes. Then they trained a neural network to take the 4-dimensional NLOS radar encoding as input, and draw similar bounding boxes.

The paper states that their network incorporates both tracking and detection, although the tracking description is brief.

“..our approach leverages the multi-scale backbone and performs fusion at different levels. Specifically, we first perform separate input parameterization and high-level representation encoding for each frame..After the two stages of the pyramid network, we concatenate the n + 1 feature maps along the channel dimension for each stage..”

It seems like, for each frame, they store the output of the pyramid network, which is an intermediate result of the entire architecture. Then they can re-use that output for n successive frames, until there are enough new frames that it’s safe to throw away the old intermediate output.

The paper includes an “Assessments” section that compares the performance of this approach against single-shot detection (SSD) and PointPillars, two state of the art detectors for lidar point clouds. They find that their approach isn’t quite as strong, but is within a factor of 2–3, which is pretty impressive, given that they are working with reflected radar data, and not high-precision lidar data.

I’m particularly impressed that the team published a webpage with their training data and code. There’s also a neat video demo. Check it out!